This is a L-O-N-G post but I wanted to get everything down in one place. Prepare a cuppa!

The key reason many of us went on this tour to Japan was due to our involvement with the State Emergency Service in our state of New South Wales. As volunteers, we help with storm and flood victims, as well as crowd control as the need arises. Whilst the vast majority of our trip to Japan was site seeing, there were a number of occasions we turned to our (voluntary) work and interests.

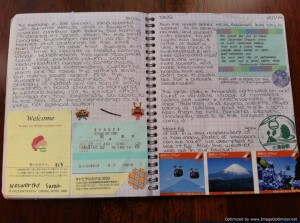

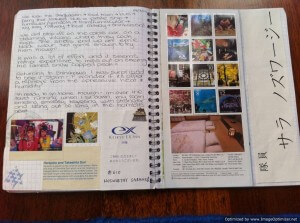

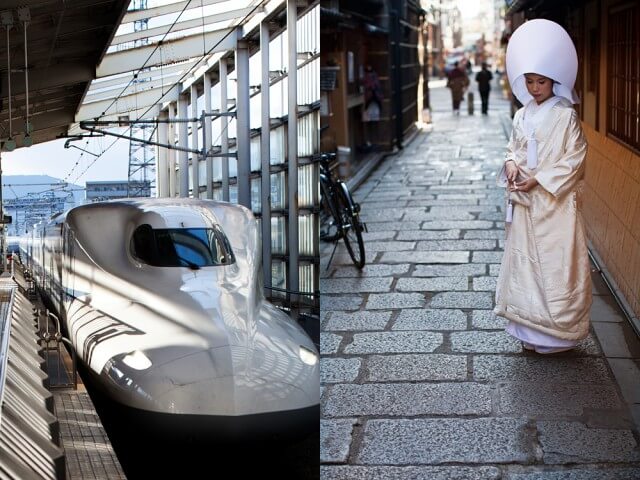

Our first exposure to disasters in Japan was through our Sister City program, between Bankstown council and Suita City outside of Osaka in Japan. This city council arranged for two days of talks and activities, which included visiting a local fire and paramedic station, travelling to Kobe to see the museum there (more later) and many talks and slides from a number of different organisations involved with disaster response. By and large, Japan has a very formal and paid work force involved with disaster assistance. That being said, there’s also a very large again population that seem engaged in a number of voluntary capacities in day to day life (guides at sites and museums) as well as in times of crisis.

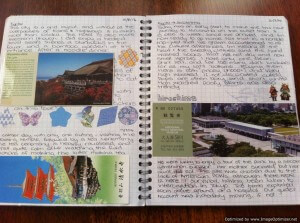

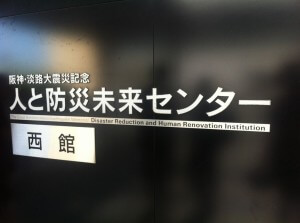

In Kobe, where there was an earthquake in 1995 (known as the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake) there is the Disaster Reduction and Human Renovation Institution. This modern glass water front building offers a number of museum exhibits as well as auditoriums that show the effects of the 1995 earthquake, with footage taken from about the city. It was the first time I felt unsettled and chose to look at the ground than continue to see the images of damaged buildings. I have a strong interest in human disasters (such as the Holocaust) and this is the first time I remember being so moved by something that I can no longer watch. There was no blood or gore, but my empathy meter was on overdrive, further hindered by not being able to rationalise this sort of event. It’s natural, and it could and does happen regularly in Japan – where I was. There’s no one to blame – there’s only preparations that can be made.

The Kobe earthquake, as I know it better, marks as a great learning point for Japan. Our guide was clearly impacted by the earthquake, and outlined a number of learnings that came away from it. “Back then” there was very little in the way of formal reimbursement for the loses suffered, now Japan offers up to 3 million yen per person. After such an event, people are moved in to temporary housing (which we got to briefly see ‘up north’). In Kobe, people were assigned homes based on a lottery system, however the guide says that people have learnt that this breaks down existing communities. He also mentioned that the average stay is 6 months, but the longest stay was 5 years! Can you imagine that? And that the temporary housing took 3 months to establish. So where did people take refuge until then?

Interestingly to me, the whole disaster response movement is centered around schools. When I thought about it, it seemed logical! They are managed by the same government bodies that assist with disasters (the prefecture level, I think, but in Australia, it’d be the state, which also works nicely). We learnt from our talks at Suita City Hall that schools contain locked sheds full of materials suitable for search and rescue, as well as temporary needs. So in the event of an earthquake, people head to school halls, and came out in school halls. Only the Japanese could make this seem so orderly – they still take off their shoes before entering their patch of ground for sleeping!

How did Kobe rebuild? In many cases, apartment blocks attempt to rebuild a 7 storey building into 10 storeys, to help finance the build by selling to more people. Obviously this strategy works in earthquake prone areas, but in Takata (north of Fukushima prefecture) the issues with flooding and tsunamis don’t make the solutions as simple. Nonetheless, this rebuilding takes time, and people do move away. As a result, shops suffer and close too.

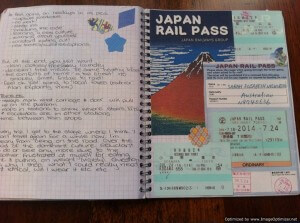

What to do in an earthquake? We learnt that after a certain year (maybe 1991?) all buildings have been made to earthquake standards, including glass that doesn’t shatter as dangerously. The advice is to move above the third storey of concrete buildings that are strong enough. We also saw signage used to denote a ‘safe place’ to evacuate to in the event of an earthquake or tsunami. Japan is flush with underground shopping malls and countless subways lines (private and publicly owned), which of course are at serious risk of tsunami flooding. Actually we went in a simulated earthquake ‘lift’ (elevator) which pretended to be in a shopping centre with access to the basement floors.

Whilst in Kobe, we watched a video on the impacts of the 2011 tsunami, and saw the township we would visit later in the trip (though at the time I didn’t know this!). My notes immediately after the video presentation, showing three years since the tsunami, had me wondering if it was even ‘worth’ rebuilding. After three years, most things were just flattened, with the debris all cleared, and I know now, a great many building flattened, despite surviving.

I also learnt about liquification, which happens as part of an earthquake, where underground water and sand based soils mix, and water often rises to the surface. If homes and buildings don’t have sufficiently deep foundations or ‘stilts’ they risk being destroyed by the earth’s movements. There’s some great (kid friendly) examples of how this happens in most of the museums we went to!

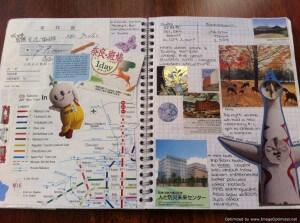

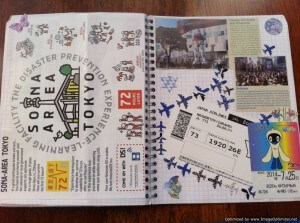

It seems the greatest level of education about natural disasters is aimed at children, with most museums we went to (one in Kobe, one in Kyoto and one in Tokyo) having a strong school based focus. To think there’s a mascot for the tsunami centre in Kyoto! Seriously – only in Japan!

After every earthquake, the government is obliged within three minutes to release a tsunami warning, which includes the suspected ‘height’ of the wave. In the case of the tsunami in 2011, the models didn’t accommodate magnitude 8 or 9 earthquakes, and therefore predictions were woefully low. As an engineer, I didn’t buy into the ‘they should have known’ or ‘they should have told us’. As I discussed with S&A (my mates on the trip), firstly magnitude is a logarithmic scale – it gets bigger fast! I can totally see which ever bean counters ignoring the possibility of the wave heights with a high magnitude quake being of a level so devastating they couldn’t imagine. If someone told you a 15m wave was coming, when in recorded history there’d never been a wave this high, then I can imagine the public’s response could have been even more lacklustre. In the 2011 case, the initial reports were for a 3m wave, later upgraded to 6m, in any case, there was a 5m sea wall, so many people felt that the impacts of the tsunami would be minimal. It goes without saying the level of devastation that was caused when the true wave came.

Whilst in Suita City, we were given a glossy 45 page A4 booklet all about disaster preparation, in English. Whilst some of the tour ‘wished there was more said and done about natural disasters for tourists’, I thought it was amazing to have this (evidently) costly publication in English, as undoubtedly it’d be in other languages. Japan, unlike much of the world I’ve travelled to, doesn’t often ‘worry’ about languages of others. If anything, there’s sometimes Korean, Chinese or English, but even still, many products don’t feel the need to carry any translations (I suppose just like Australia!).

In the event of a natural disaster, there’s a fantastic voicemail system, where you can use a pay phone to leave a message attached to your landline phone. That way, other people can ring the number and check if other people from ‘home’ have left a message. I’ve never heard of a system like this, and it just BLEW me away to have this organised. In Tokyo, we saw a short animation of a disaster, and saw the kids and the parents using this system too! Even more surprisingly was in a super technical nation, the public pay phone lines are given priority coverage after a disaster. And yep, we saw payphones all over – much more so than in Australia now.

In the course of our travels, I noticed little preparedness measures taken. Exit signage was often on the floor, or knee height in the wall – made sense to me, as you often evacuate on your knees if there’s smoke. Makes the ceiling and doorway mounted ones in Australia seem nonsensical (though these also existed in parts of Japan). Every hotel room we stayed in had a torch mounted to the wall. Not once did I see a torch missing – so tourists are honest (or torches values are decreasing in the smart phone era?)

All the museums covered the need for three days (72 hours) supply of food and water. In Tokyo, there was a collection of different ‘packs’ available around the world. The smartest (in my opinion) formed the stuffing of a teddy bear (which may have also had backpack straps). As a souvenir of our time in Suita City, we were given a high nutrition food bar (about one and a half times the size of a matchbox?) and a wind up torch – almost perfect for our purpose.

I think I’ve reached my saturation point for this post – which isn’t to say I won’t randomly realise things I’ve forgotten I wanted to document. But here it is for now…

Does your city have an evacuation plan? What makes you ready for a disaster?